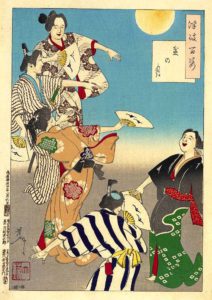

The middle of August brings some of my favorite days, all based in memory. First, there is Obon, the summer festival of Japan that honors the dead. In some prefectures of Japan, Obon is celebrated in July, and in others, in August, always around the 15th. For me, growing up in South Florida, it was August, for that’s when the Morikami Museum, west of Delray Beach, used to celebrate it. It was always hot, and we would smell of pennyroyal, to keep the mosquitoes at bay. There were often thunderstorms in the afternoon, because that’s the typical weather pattern here in summer. But there was something unforgettable about the dark grey sky behind the tall pine trees mixed with the heat and the humidity and the thundering sound of taiko drums, the electric lanterns hung between the trees, and the elevated yagura platform, painted in red and white stripes, around which the dancers would dance their mysterious Obon dances, like this one: the Coal Miners’ Dance, in which the dancers journeyed around the yagura with a shoveling motion, taking a few steps forward and almost just as many back. Their progress around the yagura was always very slow and languid: the rhythm of late summer.

At nightfall, fireworks, and then the setting sail of hundreds and hundreds of floating lanterns on the water: these are the ancestors, returning home as the festivities conclude, home to their distant shore.

I seem to have an affinity for any holiday / holy day that connects us to those who have passed. Cemeteries and church yards do not bother me and I talk to my beloved dead on a daily basis, which all may have a lot to do with the way I was raised. The dead never seem very far away. Just a slight shift in manifestation; but these people are all still very much part of my daily life.

And so I love Dia de Muertos, which has grown so popular, and I love Obon, which is not quite as popular, but which serves a similar purpose. The Morikami no longer celebrates Obon proper––they’ve moved it to the cooler, drier month of October and anglicized it to “Lantern Festival,” and they’ve moved all the traditional dances, which are meant to be danced beneath the dome of the sky, to a spot beneath a roof. All with the best intentions, of course, but in doing so they’ve whitewashed the experience, sanitized it, made it safe and out of touch with Obon’s authentic spirit.

Ah, but still I have my family’s Italian traditions for this time of year… and what follows here is a reprint of last summer’s Convivio Book of Days chapter for Ferragosto, called “A Ferragosto Recipe.” I loved re-reading it so much, I thought you might, as well. As for the cucuzza longa in the recipe, if you’re local, you’ll be happy to know that I bought some today at Rorabeck’s Produce on Military Trail west of Lake Worth, near Atlantis, and my sister bought some at Doris Market west of Boca Raton. I’d recommend a meal on the 15th of my family’s Ferragosto Recipe, along with some crusty bread and a nice pitcher of red wine with sliced peaches. E buon appetito!

A FERRAGOSTO RECIPE

August 15, 2018

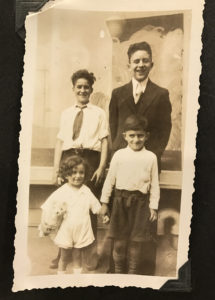

The Fifteenth of August brings my maternal grandmother’s birthday, and since she was born on this day, the Feast of the Assumption, my great grandparents named her Assunta. American neighbors sometimes called her Susan or Suzy, but that just never sounded quite right to me in naming a small, feisty Italian woman who spoke broken English. Grandma always was Assunta, or, as Grandpa would call her, Assu.

This Feast of the Assumption, which marks the ascent of the Virgin Mary body and soul into Heaven, marks other days, as well: the Dog Days of Summer are over today, and it is the great Italian summer holiday of Ferragosto. The waters today are blessed by priests and so most Italians close up shop and head to the sea, some to soak their aches and pains in the blessed waters and others just to swim or float or get a suntan. One thing is certain: work is not a priority today. (We could learn a lot from the Italians.)

Grandma’s birthday and Ferragosto mean, for us, a simple supper of cucuzza longa simmered with eggs. It is hearty peasant fare that is quick and easy to prepare, which makes it the perfect sustenance for the evening of a hot day in late summer, especially when it is paired with a crusty loaf and some wine––perhaps a sparkling white or a rosé, or maybe, if you have someone like Grandpa in your life, a pitcher full of the finest summer peaches, sliced, with red wine poured over them and set in the refrigerator for just a few minutes before dinner is served. This, anyway, will be our Ferragosto dinner. I encourage you to join us.

You’ll need to first get hold of cucuzza longa. This translates to “long squash” and in fact these past two years I’ve found them in markets labeled as just that. They are not a squash at all, but actually an edible gourd, which, left to their own devices, will grow to two or three feet in length and might end up straight as pins or in curls like snakes. In markets, though, where uniformity is prized, chances are you’ll find them looking just like the ones in the photo above. For the locals: I found ours at Doris Italian Market in western Boca Raton (there are a few locations in South Florida; perhaps one near you). You’ll find them, too, at Rorabeck’s in western Lake Worth. Whether you call them Long Squash or Cucuzza Longa, this is not a vegetable you’ll typically find in the supermarket; it’s definitely a specialty market thing. In a pinch, you can substitute zucchini… but the cucuzza is different and so much better.

Here’s Mom’s recipe to prepare your traditional Ferragosto dinner. She learnt it from Grandma, who learnt it from Mom’s Great Grandma, and so on and so on… which is what I love about a meal like this: It’s not just dinner; it is, as well, a communion with others across time and space, and there is powerful magic in that.

F E R R A G O S T O S U P P E R

3 cucuzza longa

1 large onion

olive oil

1 can crushed tomatoes

8 to 12 eggs

1/2 cup (or more) grated cheese: Romano or Locatelli or Parmigiano-Reggiano

flat leaf parsley, leaves removed from stems

fresh basil

salt & pepper

Wash and peel the cucuzza using a knife or a vegetable peeler, then cut into thick slices, each slice about 3″ long (you’re cutting lengthwise with the cucuzza, as opposed to slicing rounds). Chop the onion roughly and in a large pot, sauté the onion in olive oil until translucent and just beginning to brown. Add the crushed tomatoes to the cooked onion. Let simmer about 10 minutes.

Meanwhile, in a large bowl, beat the eggs with a whisk, then add the parsley and grated cheese. (A note here about measurements: recipes like these, handed down from generation to generation, don’t come with precise measurements. You put a handful of this, a pinch of that. As Grandma would say (though she would say it in her Lucerine dialect): The more you put, the more you find.) Once the tomato/onion mixture has simmered, add about one quarter of the sliced cucuzza, followed by about one quarter of the egg and cheese mixture. Continue layering cucuzza and the egg mixture until everything is in the pot. Add a handful of fresh basil leaves; season with salt and pepper. Simmer, covered, without disturbing, until the egg is set and the cucuzza is tender (about an hour, maybe less).

All the ingredients, in the pot, about to be simmered.

This one-pot summer meal will serve 6 to 8, especially if it’s served alongside warm, crusty bread, and perhaps a simple salad of escarole dressed with olive oil, wine vinegar, and salt. It’s delicious. And it was on our table pretty much each and every one of Grandma’s birthdays. Grandpa certainly loved it. He would have eaten his Ferragosto supper and then made a simple hand gesture, his finger pushed into his cheek with a forward twisting motion, proclaiming it Saporite!