It’s Valentine’s Day, or, more properly, St. Valentine’s Day. We rarely use that “saintly” descriptor nowadays, but there have been two St. Valentines in history. No one is quite sure which of the two is celebrated today. Our celebration is most likely a combination of them both. There was a Roman priest called Valentine who was martyred on the 14th of February, 269, for giving aid to persecuted Christians before becoming a Christian himself, but there was another early Christian martyr called Valentine who scratched a message on the wall of his prison cell before his death. The message was to his beloved, and he signed it Your Valentine.

One thing we know for sure about Valentine’s Day is people love it and also love to hate it. Let’s face it: Valentine’s Day is an easy target: it’s sappy, it’s sweet. But there are times when these qualities are just what we need, and certainly they are better options than the petty bitterness that has come to dominate our days. I think so, anyway. So go ahead: indulge your sweetheart. Be a little foolish. Make the day sweeter. And where love takes root, let it grow.

St. Valentine’s Day is thought to be honored not just by us humans, but in nature, too: It has long been considered the day that birds choose their mates for the year. Robert Herrick, our convivial Book of Days poet, alludes to this belief in this poem from 1648:

Oft have I heard both youths and virgins say

Birds choose their mates and couple, too, today

But by their flight I never can divine

When I shall couple with my Valentine.

In England and Scotland, in Herrick’s time, and for centuries up until the 1800s, the celebration of Valentine’s Day often began the evening before. Young men and women would take part in a lottery, of sorts, on St. Valentine’s Eve, drawing names out of a box. The person that luck gave to you in this lottery would be your Valentine, and small tokens would be exchanged. Many weddings were known to come out of this St. Valentine’s Eve sport.

There are a few traditions of romantic divination that have come down through the centuries for Valentine’s Day, as well. The first unmarried person you’d meet on Valentine’s morning might just be destined to be your bride or groom, for instance, as the case may be. John Gay describes this in his poem “The Shepherd’s Week: Thursday; or, The Spell”… which happens to be a burlesque on the pastoral poems of another poet of the same era (early 18th century). It starts with that same allusion to birds finding their mates on Valentine’s Day:

Last Valentine, the day when birds of kind

Their paramours with mutual chirpings find;

I early rose, just at the break of day,

Before the sun had chas’d the stars away,

A-field I went, amid the morning dew,

To milk my kine (for so should housewives do)

Thee first I spied––and the first swain we see,

In spite of fortune shall our true love be.

Destiny or not, go ahead: share some sweetness with the ones you love this Valentine’s Day. And why not be outlandish and extend that to others beyond that circle, too. I was brought up to be kind and respectful and to follow rules for the greater good and the benefit of all and these are qualities that have fallen out of favor, or so it seems. But I am persistent in doing what I think is right, and I guess I always will be.

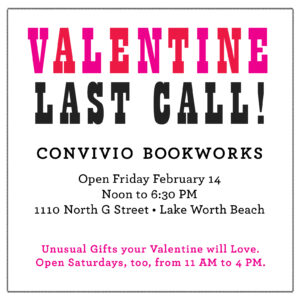

THE SHOP IS OPEN FOR VALENTINE’S DAY!

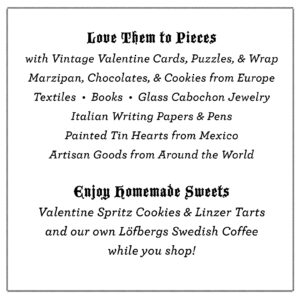

We’re open today, Friday, February 14, from 12 noon to 6:30 PM for your last call Valentines. Find us at 1110 North G Street, Lake Worth Beach, FL 33460. You’ll love what we have in store for you (it’s not your usual stuff)! We’re also open tomorrow for our usual Saturday hours, too (11 AM to 4 PM).

SHOP OUR VALENTINE SALE!

At our online catalog right now (across the board; not just on Valentine’s Day items) use discount code LOVEHANDMADE to save $10 on your $85 purchase, plus get free domestic shipping, too. That’s a total savings of $19.95. Spend less than $85 and our flat rate shipping fee of $9.95 applies. St. Patrick’s Day is coming and we have lots of new items focused on shamrocks and Irish literature and more. CLICK HERE to shop; you know we appreciate your support immensely.