It is the feast today of St. Anthony the Abbot, Sant’Antonio Abate in Italy, where this day is a very big deal. . . mainly for the food. It is the traditional day for dispatching the family pig, which is not a very good day for the pig, of course, but which brings on a feast of epic proportions revolving around dishes whose main ingredient is pork. It is a day of salting, curing, and smoking, to make sausages and salame and prosciutto and pan con i ciccioli––bread baked with pork cracklings––which is something I loved as a kid but which we rarely eat nowadays in our more health conscious world.

This is not the guy most of us think of when we hear the name “St. Anthony:” that Antonio––the one that is the subject of so many statues outside homes in Italian neighborhoods–– is St. Anthony of Padua. He lived about a thousand years after St. Anthony the Abbot, and his feast day is June 13. But back to the food. The fact that St. Anthony the Abbot’s feast day is associated with so much feasting is a bit of a paradox, for Anthony himself was an ascetic who disposed of all his worldly possessions so he could head out to the desert of Egypt to live his life in simple prayer and contemplation. He lived mostly on bread. The traditions in Italy that have arisen for his day probably have more to do with timing that with anything at all about Sant’Antonio himself, for winter is the traditional time to butcher animals and prepare their meat: better this, thinning their numbers now, than to risk their starvation in the cold hard months of winter yet to come.

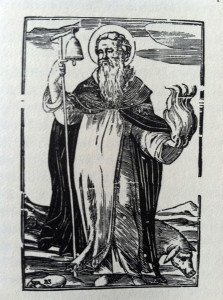

On the eve of Sant’Antonio, which was last night, there are many great bonfires throughout Italy, especially at crossroads and in church piazze, to warm the cold winter’s night. And while St. Anthony’s Day may not be a very good day to be a pig in Italy, still, St. Anthony the Abbot is a patron saint of domestic animals, and as their protector, he is always depicted with a pig at his side. He also happens to be a patron saint of bakers (perhaps the same bakers who came up with pan con i ciccioli). This, no doubt, because he ate so much bread.

Image: Today’s Convivio Book of Days image comes with a built in little game: Find the pig. Click on the image to make it larger, then look for the disjunction here in “Virgin and Child with St. Anthony the Abbot and a Donor” by Hans Memling. Oil on panel, 1472. National Gallery of Canada, [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.